OK, I'm calling it

When have you made a prediction, and got it wrong? Or right?

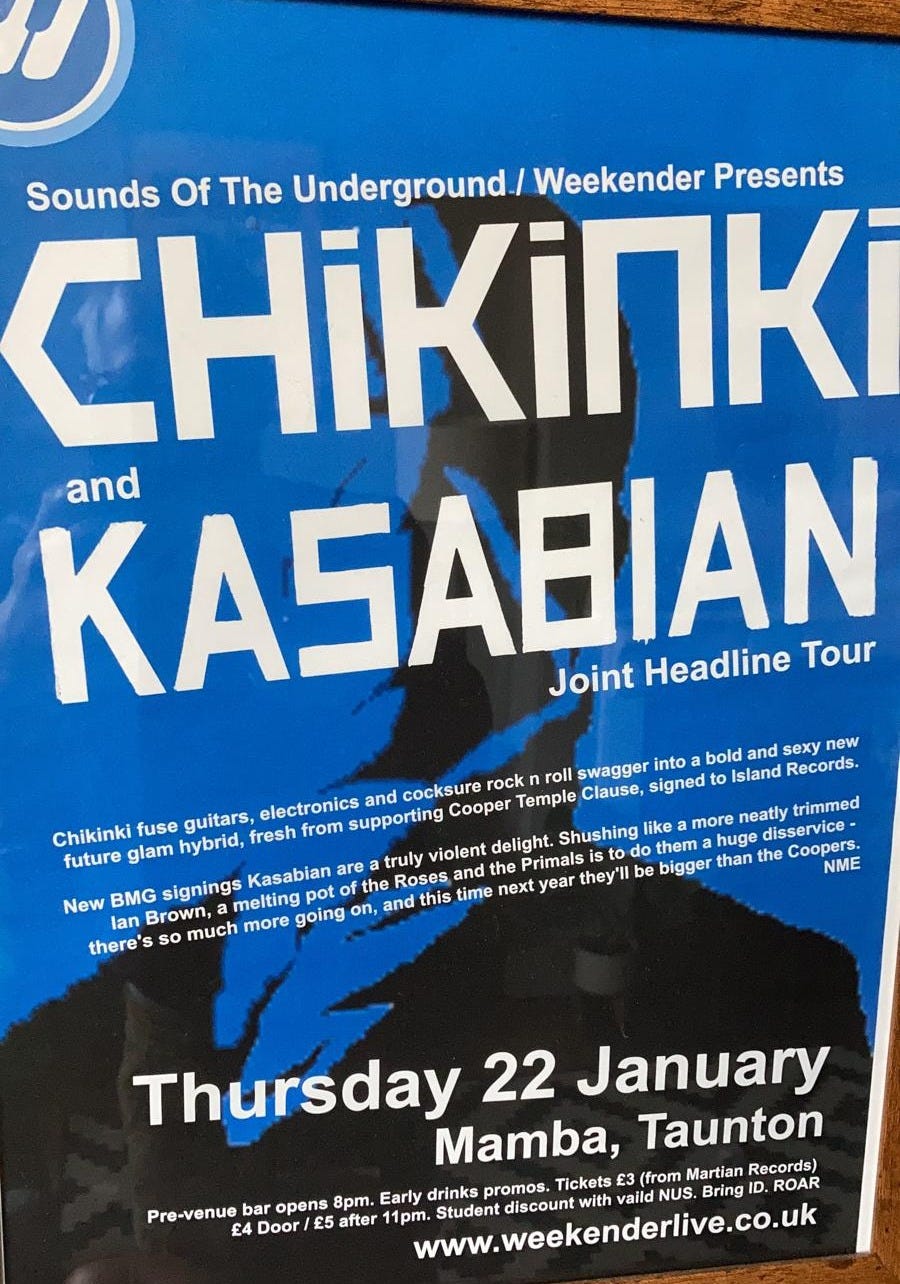

Twenty years ago I made a prediction. Kasabian – who I saw supporting Chikinki at a Weekender night in a basement bar called Cafe Mamba in Taunton – were going to be huge. And I was right.

True, I also over the years predicted big things for Buffseeds and Electric Soft Parade and Duke Spirit and Psychedeliasmith. And I was wrong about them. But who remembers when you’re wrong?

Well just ask the late Paddy Ashdown about eating his hat or see if Rory Stewart can sum up in words how big a wally he is feeling about declaring Kamala Harris would “win comfortably”.

Why do they do it? Why does anyone? I had a journalist pal ask me over the weekend to make a public mea culpa for calling the US election wrong. When I pointed out that I had not “called it”, he berated me for the cop-out of going all the way to America for a week only to declare it “too close to call”. Which it was. The polls showed that it was close. And the more voters I spoke to, the less sure I was about which way it would go. And that’s fine.

We don’t need to wish our lives away predicting things. Calling it. The fun of politics (or for that matter sport) is seeing what happens. Sometimes David beats Goliath. Sometimes he doesn’t. Wait and see.

Working for a broadcaster based in the UK, I also felt it was important to explain to British listeners why so many people would back Donald Trump (who just one in six Brits wanted as president). So hearing from real Americans concerned about immigration and the cost of living might have helped with the understanding, if not predicting the outcome.

Nostradamus started it. And there was definitely a time when being the first to “call it” on Twitter was a thing, and followers would follow. And obviously if you are willing to put your money where your mouth is with a bet on your predictions, you can make a financial gain. But come on.

My only other successful prediction wasn’t even a prediction. In May 2016 I wrote a column in The Times when Theresa May was at her peak, having called a snap election and marching unstoppably towards a huge victory. I wrote:

“Don’t you just love Theresa May? She’s brilliant, isn’t she? The way she leads and speaks and has a head. I’ll whisper it — and don’t tell No 10 — but I think I might have deleted the email where everyone decided that Theresa May was wonderful. She’s not that good. She really isn’t. Or at least not as good as the polls and the pundits and the giddy vox-pops would have us believe.”

Now, she went on to lose her majority. Which I didn’t actually predict. But I was much less surprised than those who had confidently predicted a landslide while refusing to question it. And other people praised me for calling it. Which I hadn’t, not really.

People who make public predictions are also even more likely to ignore evidence which contradicts their forecast, or over-play things which reinforce it.

It is one of the things I have enjoyed about being at the BBC. The impartiality rules do make you take the story of the day, and turn it upside down and examine it from the other side. Does everyone think it is bad? Will everyone find that offensive? Who will really get the blame?

I love to ask a guest: “Fine you don’t like X or Y, but can you explain why so many people do?” They often can’t. That’s more interesting than me acting like a freelance returning officer, declaring the result ahead of time.

Yet the desperate rush to do it will continue, especially in an increasingly fractured media landscape where podcasts and social media become echo chambers for what people want to happen rather than analysis of what is happening. People will keep trying to call it. That’s one prediction I am willing to make.

When did you call it?

I am really keen to know your brags about when you called it right. Or got it spectacularly wrong and haven’t lived it down.

Started your Christmas shopping yet?

Only 43 days to go… The perfect gift for that political nerd in your life. Or someone who isn’t into politics but likes short, interesting, funny, moving chapters. Or someone who likes cartoons. Look just buy a dozen copies and then work out who to give them to. Order now you Grinch.

I spent ages lobbying online for people to vote 'tactically' in named seats in (I think) the 2015 GE, supposedly to keep UKIP out I think (my brain seems to have deliberately deleted the details). Pretty much every seat I made confident predictions about went a totally different way and one of my friends brings it up at least once a year. I don't predict anything any more.

I love the line about 'freelance returning officers'. And tbh it's a pet peeve of mine when British political journalists/podcasters suddenly pretend to be profound experts on US elections every four years, when I can see they're just regurgitating whatever Nate Silver/Matt Taibbi/Dave Weigel said the day before. Very irritating.

I called the 1992 election wrong because I was on the doorstep and didn’t hear about the Sheffield rally for days. (Nor did most voters, it is a media myth that it lost the election.)

I normally bet on the thing I don’t want to happen because I can’t lose; this year I was too embarrassed to go in to the bookies to bet on Trump.)